Finite State Automata

I’ve come across finite state automata (also known as finite state machines) in multiple different contexts. After all, regular languages are context-free (this joke will not be funny until later). One of the more interesting aspects of computer science is how different topics pop up across different areas that appear to be totally unconnected.

FSA in Circuit Design

The first time I encountered finite state machines was in a logic and design class. In this context, state machines arose naturally as a model for a simple computation. Here’s a quick example:

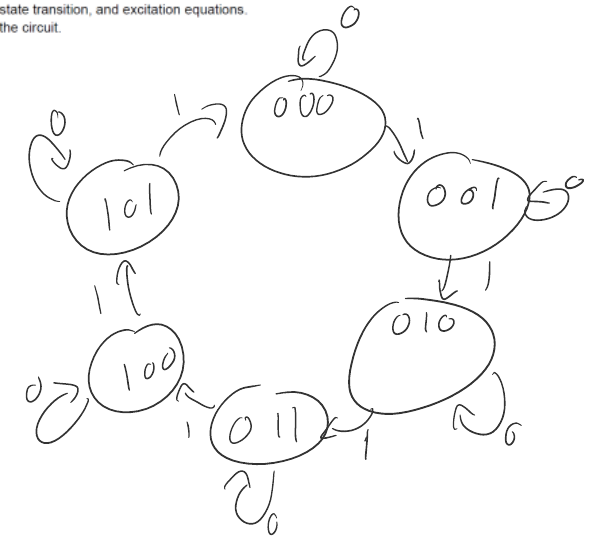

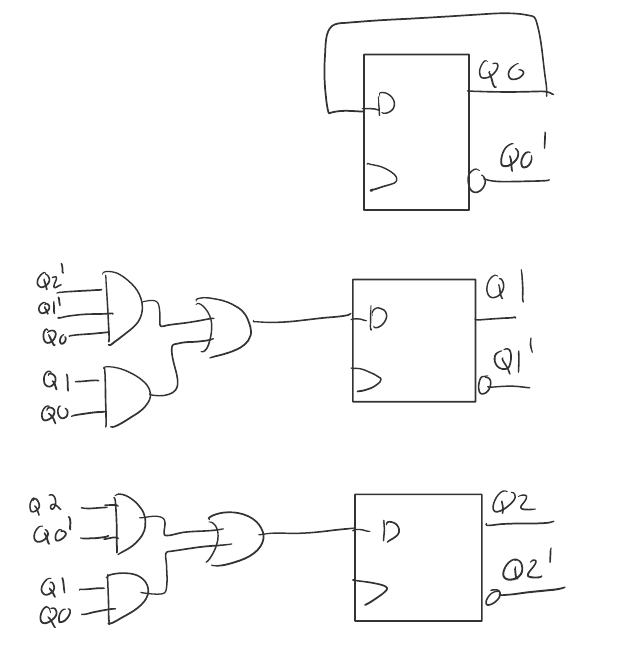

Problem: Design a 3-bit binary counter with counting sequence 0,1,2,3,4,5,0,1,… This seems a simple enough problem. Here’s my sloppily-scrawled solution:

If the clock ticks 1, increment the counter. Once 5 has been reached, wrap back around. In this context, a FSM has been used to informally describe the structure of some circuit, but it only appears to matter for human context. Indeed, the implementation of the FSM in hardware was more based on a truth table and Karnaugh map simplification then the structure of the FSM.

Thus, in this case, FSM were a useful tool to describe the overall structure of a problem, but leaves implementation details to a formalized method. The second place I encountered FSM is a similar story.

TCP Specifications

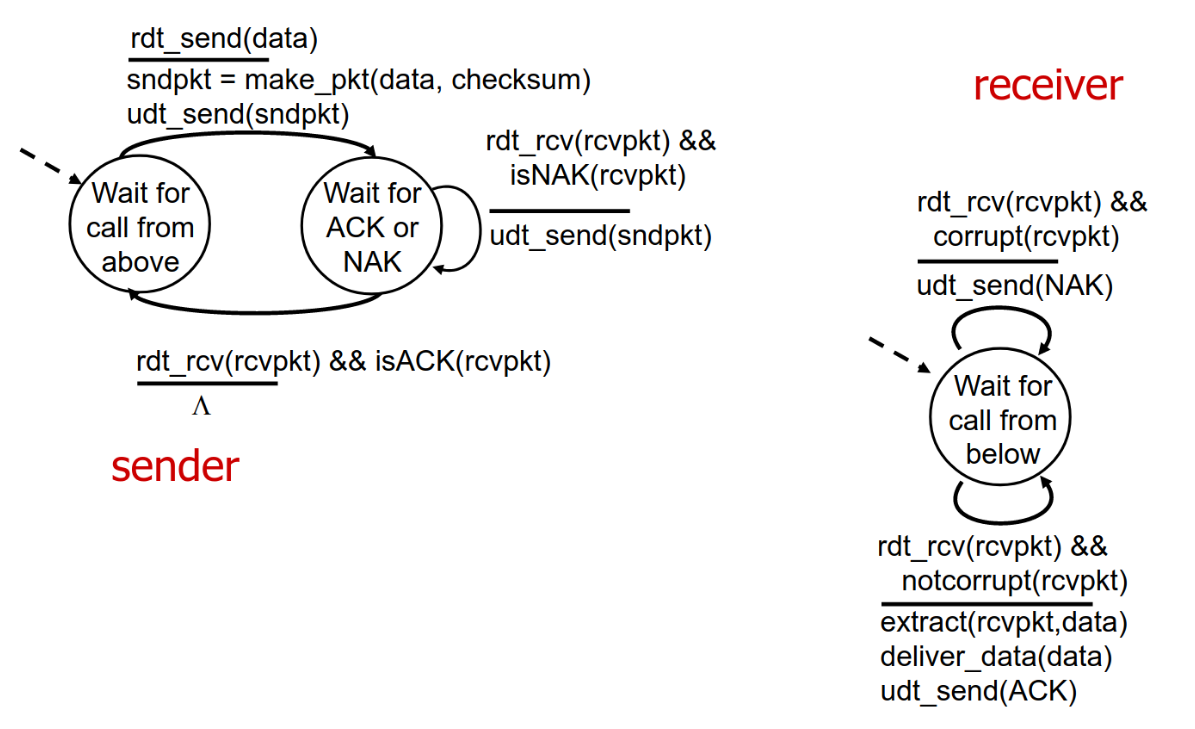

For my networks class, I had to understand (and write!) an implemention of the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). TCP is used for pretty much every Web transaction where reliability is important, and is implemented at the operating system level via Unix sockets. The specification for TCP is laid out in the RFC. Although the RFC never mentions FSM directly, it does lay out a sequence of states and state transitions for TCP, beginning on page 20. TCP can therefore be implemented as a state machine. TCP is based on the principle of reliable data transfer, which attempts to adjust for network errors such as flipped bits or dropped packets (this is what differentiates TCP from a fire-and-forget protocol like UDP). When designing a rdt protocol like TCP, it becomes useful to draw a FSM for both the send and receive side, as show below.

Unlike my experience with circuity, the high level of detail provided by the FSM is already quite useful; clearly, we can just place the conditions on this diagram into a series of if-statements and let the machine loop. This use case hints at how a informal model can be used to describe the structure of a program.

Automata Theory

The next place I encountered finite state machines was in a class on theoretical computer science. Naturally, the first thing that must be done is construct a theoretical computer. A finite state automata is one of the simplest models we can use (in contrast to pushdown automata and Turing machines). To give a formal definition:

A finite state automata M is a 5-tuple (Q, ∑, δ q, F) where

- Q is a finite set of states

- ∑ is a finite set called the alphabet

- δ is a transition function

- q is the initial state

- F is the set of accept states.

Informally, a finite state automata is a set of states and a transition function, that work on some “alphabet”. Let’s make this more real.

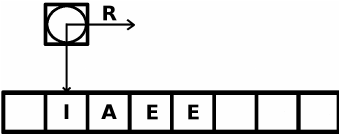

Imagine we have returned to the Stone Age of computing, and all we have on hand is a infinite tape for input, a “head” processing unit that can read from the tape, and a machine that threads the tape past the head. Additionally, the machine has a patient “operator” that knows what to do for every character that the head reads in from the tape. This theoretical machine is (surprisingly?) a very useful model for computation!

Regular Languages

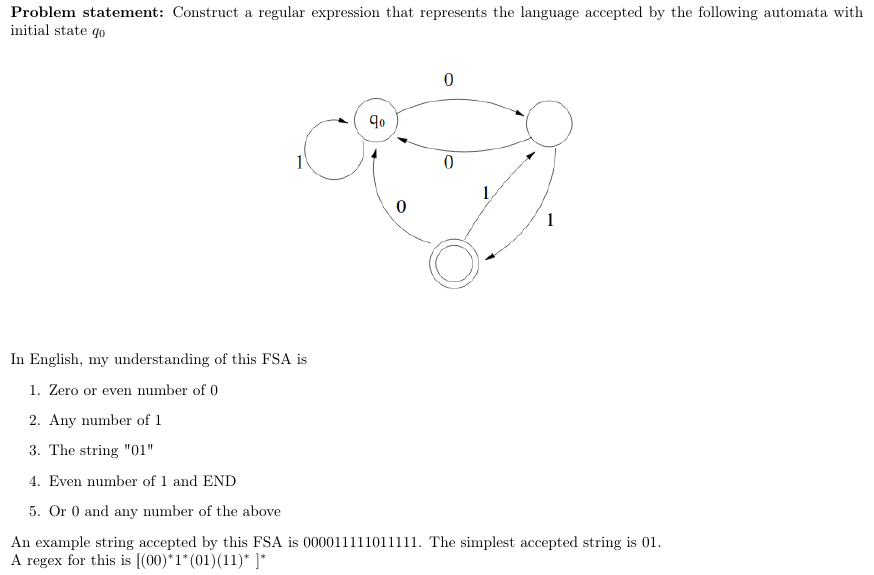

As it turns out, the type of problems that a FSA can solve are known as regular problems. Generally, problems are called languages, where the elements of the language are solutions to the problem. This is a useful construct throughout computability and complexity theory. Now let’s use this theory for something, that something being everyone’s favorite problem-solving method of “dude, just use a regex”. Regex, short for Regular Expression, is a much-feared method of string matching, on account of it’s somewhat difficult syntax. However, a landmark result in language theory is that regular expressions are actually equivalent to finite state automata! That is, a regex exists if and only if you can construct a FSA that can compute it. The proof is quite interesting, but it’s much simpler to use nondeterminism (magic!), which will hopefully be discussed in a future post. Let’s give a concrete example.

Although regex syntax can be frightening, this simplified version has only two symbols, * and implied concatenation. The * symbol simply means “any number of,” and the concatenation is just “these must be next to each other on the tape”.

So how does our idea of a FSA help us in figuring out a regex? A common technique in FSA-programming is to imagine yourself as as the all-knowing “operator” that makes decisions based on what he or she reads from the tape, one at a time. This is very helpful when considering more complex regex that may be less trivial to write out in a few lines of English.

Bonus Section: Context Free Languages

In order to justify my joke at the beginning (“After all, regular languages are context-free”), I’ve got to explain it. Essentially, imagine your FSA and add another tape; this time, we’ve made some technological progress, and can now write to this tape. This tape is a stack, meaning that it’s a first-in-first-out queue. Other then that, it’s the same thing as the FSA. We call the languages decided by these machines context-free, and the machines themselves pushdown automata (after the stack). Clearly, our new machine is more “powerful” then our FSA, and can do anything the FSA can do (and more!) Thus, all regular languages are also context free! I’ll save the implications of this for a later post, but now you can at least pretend to laugh.

Wrapup

In summary, FSA are pretty neat, and pop up in all sorts of cool places. Honestly, each of the topics covered today deserve a post all on their own. The purpose of this post was to document my “hey, I’ve seen that before” feeling, and hopefully connect a few neurons in my own head, as I’ve found relating seemingly-disparate topics is quite good for digging deeper into it. Next up is probably nondeterminism, which is probably my favorite computer science “hand wave” and also my favorite justification for forgetting to show my work.